San Marcos Pass

For many years, an Indian trading path crossed the Santa Ynez Mountains, which we know today as San Marcos Pass. It crests at 2,225 feet above sea level. Its name memorializes Fr. Marcos Amestoy, the monk, who, while in charge of the Mission, supervised the building of the mission dam, waterworks and filter houses between 1804 and 1813.

In the war with Mexico, Col. John Fremont marched his troops southwestward to claim American territory. He camped near the summit during a raging rainstorm on Christmas Eve of 1846 near Laurel Springs and Painted Cave village. He descended through Kinevan Canyon and Catlett Canyon (now Rancho Del Ciervo Estates near Patterson) to the Goleta coastal floor.

Stage coaching was the central activity at San Marcos Pass for the period from 1860’s onward. In an attempt to shorten the route to the north, a group of six doctors and lawyers determined to establish a toll road over the mountains at San Marcos Pass in 1868. Hiring Chinese coolies and using picks, shovels and black powder, they roughly followed Fremont’s trail. Travel began at what is now Hollister Avenue near San Marcos High School and ended at Mattei’s Tavern in Los Olivos, where a narrow gauge railroad to San Luis Obispo began.

At the 1500-foot level, a stretch of bedrock forced the road builders to chisel four-inch-deep ruts for stage wheels. Some of the ruts, known as Slippery Rock, are worn as deep as 14 inches. They can be seen today, though the land is closed to public access. Concord wagons drawn by 6 horses were the popular conveyance.

Patrick Kinevan was hired to work at the central route station at Chalk Rock, under present day Lake Cachuma. He manned a gate at a bridge over San Jose Creek (near Cold Springs Bridge) with fees of $1.00 per horse, $2.50 for a stage, 25 cents a head for horses and cattle and a nickel a head for sheep. The terrain slowed speeds for stages, which led to a problem with banditry.

Kinevan built a house near the tollgate in 1872, which he called Summit House. He kept a large barn and horse pens. His wife, Nora, served meals to famished travelers for the next 25 years. In 1890, the county purchased the Turnpike Road and opened it to free travel. Soon Nora’s dinner station had competition from a roadhouse in Cold Springs Canyon known as the Cold Springs Tavern. Cold Springs Tavern may have been the hideout of Dr Lawrence, said to have murdered his wife in Los Olivos. It also served as a gambling joint during prohibition. Today it houses a restaurant described as a stage stop.

Banditry helped establish many buried treasure tales. There may be at least some truth in the tales. A dying bandit claimed he buried treasure “under a rock on the south side of the summit where two creeks meet.” Hundreds have searched the area. In 1913, Kinevan’s son Tom found a gold $50 piece near a creek bank.

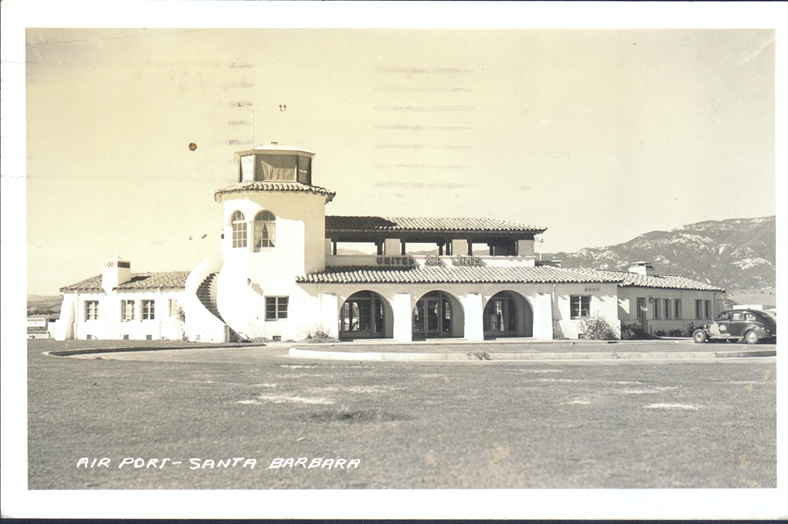

In 1892, Slippery Rock closed, forcing the road to move to a new route known today as Old San Marcos Pass Road. Actually a boon, the trip shortened by over an hour from Santa Barbara to the top. In 1901, the first car rode over the pass, a steamer arrived and the mail stage era ended as the Southern Pacific railroad completed its coastal line, taking away their mail delivery contracts. The last stage using the Pass is displayed at the County Courthouse.

From the 1870’s to 1890’s amateur archeologists raided the Indian caves and gravesites in the Pass area, selling the Stone Age items to the highest bidders, often far-off museums. A spectacular grotto know as Painted Cave came under private ownership and was closed off with iron bars by Johnson Ogram in 1907 -preserving it for all to see. Ogram built a home a quarter mile above the cave on a high plateau. He and his wife took in boarders and began to attract health seekers because of the climate. Spring water was available and the local reputation grew. When Santa Barbara movie making was at its height with the growth of the Flying-A studio, many westerns were shot in and around the Pass.

In 1924, a group of Santa Barbara Masons established a private retreat half way up to the pass and sold 30 home sites on 120 acres. Two large concrete catch basins were stocked with trout to provide excellent fishing. The San Marcos Trout Club became a popular spot offering a private water system and paved roads. Vacationers built rustic homes mostly of logs. Seeing a need for more home sites, Ogram’s son John subdivided his 40-acre resort. Ogram’s subdivision succeeded and is now a community of more than 100 homes, many with remarkable views of Santa Barbara and the channel from its 2,500-foot altitude perch. People with respiratory ailments still seek out this location.

Homer Snyder is another settler making a mark on the pass. He homesteaded the Laurel Springs Ranch. Around 1930 George Knapp, a Chicago utilities tycoon, purchased the ranch and turned it into a retreat for Cottage Hospital nurses. He and John Ogram built the road that serves as the entrance to Painted Cave. The south exit constructed is one of the most twisted in the county with 77 switchbacks. In 1940 a forest fire wiped out Knapp’s lodge and most of Painted Cave including the Resort. Painted Cave was rebuilt, but fires came close again in 1955, 1964 and 1990.

Summit House and the original stagecoach barn were still occupied by Kinevan’s descendents when they were designated historical landmarks in 1950. They evacuated in 1955 as the Refugio Fire neared. An overzealous Forest Service bulldozer operator flattened the barn without permission. At least as bad, the burglars vandalized the house while they were away. The family, dying a few months later, didn’t get to witness the final indignity as squatters burned the house to the ground in 1972. The site is still in the Kinevan family’s hands.

Highway 154 straightened out many of the twists of the road in the 1960’s. The final hairpin turns were removed with the opening of the Cold Spring Bridge in 1963. It consists of a single 700 foot arch 400 feet above the canyon floor.

It took 8 hours to travel from Santa Barbara to Los Olivos at the turn of the last century. In the 21st century, it is easily accomplished in 40 minutes. The San Marcos Pass Highway is now designated as a Scenic Highway. It is protected by a corridor where billboards and commercial development are banned forever and shall remain one of the most beautiful roads in California.

All Rights Reserved.